|

|

Monday, March 9th, 2009 at 9:14 am

After a very long absence, here I am again. We have been gone more than we’ve been home of late. For the record, I’m pretty tired of traveling and would prefer to stay in Temux a while, but that’s not an option. So here’s the update while I can get it in.

I haven’t written since nearly the end of January. We’ve been busy. After I published the last post we took off for Antigua where we met with the Stove Team International, a group of Rotarians, a scientist who specializes in combustion, and a few latin business men who are all working together to make and distribute efficient word-burning stoves. As some of you might remember, improved wood-burning stoves is one of five technology projects we’re working on  here. The Stove Team’s most prominent stove model is quite different from the one the Peace Corp usually uses, so we thought we’d go learn about options. Turns out we met a really fun, energetic group of people, and then we kidnapped their intern, Elke…Here she is in a happy picture with us, on the hotel roof deck looking out over the city, shortly before the incident. here. The Stove Team’s most prominent stove model is quite different from the one the Peace Corp usually uses, so we thought we’d go learn about options. Turns out we met a really fun, energetic group of people, and then we kidnapped their intern, Elke…Here she is in a happy picture with us, on the hotel roof deck looking out over the city, shortly before the incident.

When working with new people, I’d say we’re most trepidatious about whether or not their “development approach” is going to match ours or not. Do these people just give away their stoves or do they charge a price for them? Are they paternalistic or working sustainably? The problem with the paternalistic approach is it works under this great assumption that if we just give a certain thing to certain people we can improve their standard of living/quality of life because they’ll have said thing. This approach assumes the people want what they’re getting, that they understand it’s inherent value, that they know how it will benefit them (be it healthwise, economically, whathaveyou) and that they’ll work to maintain/repair/replace said thing as needed. That’s a lot of assuming, too much really, so it doesn’t usually work out as smoothly as the benefactors hope. This approach also has the nasty affect of training people to receive something for nothing, which makes any future attempts at sustainable development more difficult because the people don’t want to work or contribute money when they were just given everything before. Peace Corp has to deal with this all the time. In fact, our friends had to change their site because they were sent to a town that had thousands upon thousands of euros dropped on it. After three months of trying to find work, they gave up. They realized they weren’t going to be able to work on education with the town’s people, as the people just wanted presents they felt they were entitled to. Teaching people they don’t have to work creates more problems than it solves, no matter how nice people or organizations think they’re being by “donating” said thing to said people. This is paternalism vs. sustainability.

Not only is the stove team working for the latter (sometimes hindered by the former just as much as we are), but we got into some very interesting and prolonged discussions about this topic. The problem is that lots of organizations (including, but not limited to, Rotary clubs where stove team started) don’t understand the damage they’re doing in the name of aid. This is a really hot topic for me, so I’ll wrap this up rather than bore you all with the knitty gritty details. Basically I tried to convince Nancy Hughes, the Oregon Rotarian rep., to launch an educational campaign for the rotarians–and any other social works group who wanted to listen–about this issue, at least until I get back to the states and can do it myself :)… Thing is, sometimes I am very much my father’s daughter, and if you know him, you know exactly what I mean by this. My efforts might have been a little misdirected as Nancy is already incredibly busy with the stoves (after her 2 weeks here she flew home for a day before heading out for a month in Africa to work on the same project), but she took the whole thing in stride, and she bought us lunch at a very tasty restaurant. Thanks, Nancy!

The stove team had lots of things to do that didn’t involve us, so we had some time to do something we rarely do in Antigua–sight see–as we waited for the right moment to steal away with the intern. People should come visit us because this country is really amazingly beautiful, with some cool stuff to do. So here is a picture to entice you. This mostly goes to my sister who wants to go to Mexico for her birthday, and my brother who wants to go to Belize for his honeymoon. Really guys? Really? You won’t get personal tour guides there (and I’ll probably be annoyed with you forever)…Volcanos, Mayan ruins, rainforests, ocean fronts to the Atlantic and the Pacific, mountains, scuba diving, hiking, canoing through the mangroves, kayaking, zip lining… The stove team had lots of things to do that didn’t involve us, so we had some time to do something we rarely do in Antigua–sight see–as we waited for the right moment to steal away with the intern. People should come visit us because this country is really amazingly beautiful, with some cool stuff to do. So here is a picture to entice you. This mostly goes to my sister who wants to go to Mexico for her birthday, and my brother who wants to go to Belize for his honeymoon. Really guys? Really? You won’t get personal tour guides there (and I’ll probably be annoyed with you forever)…Volcanos, Mayan ruins, rainforests, ocean fronts to the Atlantic and the Pacific, mountains, scuba diving, hiking, canoing through the mangroves, kayaking, zip lining…

Sight seeing was fun, but it was a little unfortunate all this happened so soon after our Christmas trip. The longer we’re deprived of these sorts of things, the nicer it is when they happen. Currently we’re just deprived of good ‘ole Temux. On Friday morning we finally lured Elke away from the rest of the stove team, and made it all the way to the capital of our department before the days end. We told her the going wouldn’t be particularly easy. We rolled into town on Friday morning, grabbed some fresh produce and continued to our home. Elke, who’d come in from the US on Monday night was pretty much wiped. In addition to all the travel, her body was adjusting to the food, and the altitude. The family, actually the whole town, was pretty stoked to have another gringo around. They were all disappointed when we told them she was only going to be around for about a week, but they made due with the time they had.

It was really interesting having our first visitor from the states here. We have a very small living space, and we have all these systems for storage, for food, for dishes, for washing. In the states these things seem to be relatively uniform from house to house, but all of that goes out the window when there is no longer plumbing or water. It was kind of funny to have to explain all the details of how we’ve figured out is the best way to wash the dishes at the stream. She got to try the chuj on her first night here, which was good since she was road tired and dirty and it was freezing. The weather did not put on a nice show. It has been mostly cold and rainy and rainy and cold since we made it back from the states. Though the sun did come out a few afternoons allowing us to go hiking and show her the great views. While she was suffering the cold in clothes borrowed from me, we assured her it would be warm and sunny in Quixabaj. We took off for there on Monday afternoon.

We’d given her advance warning that the road was really rough, but we were super lucky. There were only about 8 of us in the back of the pick-up. Our health technician, Aurelio was with us, and the local nurse sat up in the cabin. There were two local guys hauling a couple 150 lb. bags of corn out, which made a really comfy seat for me until they got off at their stops. the weather was amazing. The sun was shining the air was clean and crisp, but not too hot. You could see for some 40-50 miles all around us. After the rather hellish journey we had back from our first visit there, this trip was beyond pleasant. Here we all are, enjoying the ride, Aurelio our local boss, Fletch, Elke, and my view from the corn sacks.

It was just after 3 in the afternoon when we pulled up to the health center; everyone was starving. We went around buying some local produce and canned beans, as the nurse asked a town leader if he could scrounge up some tortillas. He seemed doubtful he’d find any, which was odd, considering everyone here eats them all the time. It took us probably half an hour to fix the food, and the tortillas hadn’t arrived. The nurse went to see what happened to our guy just as he walked in with a stack of cold ones for us to warm up. As he left a little boy came running in with a stack of fresh, hot tortillas wrapped in a towel. Once he left a local woman came with another steaming bundle. We went from maybe not getting tortillas to having stacks of them all over the table. It was comic, really, and every meal after that someone, or two, from the village would show up with more steaming stacks of fresh made tortillas. In the morning a girl came with a huge pot of black beans. We ate the regular Guatemalan fair, but there was a plenty for everyone.

This was our chance to share with Elke an authentic Peace Corp experience. This is really how it goes. By the time we’d eaten, all the local community leaders had arrived for a meeting. Remember, we first went to Quixabaj in September, planning to go back in November. The road collapsed so we couldn’t get there, and by the time they had fixed it was Christmas, so now it’s the first week of February and only our second time staying the night in this community. Our entire project had to be re-explained with the help of our technician, Aurelio, after all the men thanked us for returning to their community, since they thought we’d just high tailed it back to the US after our last visit. So Elke got the full shpeil. We talked with the leaders until they felt comfortable with everything, then we hammered out a very busy schedule for the next day. Oh, and though we’d planned to stay three full days, on the truck ride out Aurelio informed us he actually had to be back in to Santa in two days, so our three work days turned in to one. We had to try and get as much work done as we could in one day.

As the sun went down the leaders all headed home, leaving the three of us and one of the health employees to stargazing in the yard and learning q’anjob’al words for the night sky. It was really just pleasant. We were tired, full, and had accomplished at least a little something. We had a busy plan for the next, so with that we went to bed. And it began to rain, lightly at first, then harder and harder, until it was a full downpour hitting the tin roof of the health center. We hoped maybe it’d stop by morning.

Turns out, the rain didn’t stop the ENTIRE time we were in Quixabaj, much like our first visit actually. We were supposed to visit a community house by house that morning, but to get there we had to walk a mountainous dirt track that was sure to be treacherously slick with mud, “mejor nos quedamos en el puesto” said Aurelio. It’s better that we stay put here until the rain stops, he told us. So we stayed put. The community leader who was to be our tour guide had come by to get us, stayed to talk for more than an hour, and when the rain didn’t quit, he said he’d come back for us later if stopped raining and there was time before our 3 o’clock charla. This was about 9 am, so we had quite a while to kill.

Elke and I fixed coffees and teas for ourselves and anyone else who wanted. I settled in with my coffee and Harper’s magazine Don from the stove team had passed on to me (and the economist! what good reading, ahh…), and the guys unpacked the medical equipment crowding the waiting room of the health center. It rained and rained and rained. The rain brought cold wind with it. Turns out we accidentally misled Elke; there was to be neither warmth nor sun in Quixabaj. By 2:30 we’d had our second fill of beans and tortillas for the day, and the rain was not really letting up. Aurelio waffled back and forth about the 30 minute hike to the health talk, should we do it, should we not? Fletch and I said, “YES, we should do at least one thing while we’re here…” So we donned our rain gear, everyone, and took off for the community where we’d give the talk. We arrived 20 minutes late, because Aurelio couldn’t decide if we should go or not. Then it took another 15 minutes for the villagers to be called to the meeting.

In the mean time, the kids around the school played a came where they tried to push one another in to the gringos, and when we decided to participate by going after them, they would run away screaming bloody-murder. The latter we did just for own amusement. I mean, we needed to be entertained, too. Once their parents finally arrived and were seated, we started the health talk on what germs are and how they spread, bueno. We were about half way through the talk when the village leader interrupted to say we needed to wrap things up because they were now going to begin a parent-teacher meeting at the school. What!?

We literally did this charla soaking wet from the waist down; we’d stood in the back of a truck for 4 hours to get to this place the day before, slept on metal shelving a Cuban doctor turned into a bed about a year ago, and were leaving the following morning at 3:00am. Did they not care that we’d come all this way? In fact, they did care. They thanked us for our nice little talk, even though we weren’t allowed to finish it. It’s just that the other meeting was scheduled first (even though we didn’t know about it), just that using that transport isn’t a big deal–it’s the only thing that exists here and is better than walking for 8 hours; just that most of them sleep on wooden boards with a blankets to cover up. What we did to be there ain’t no big thang.

I was pretty thoroughly depressed as we got booted out of the school for the next meeting, and began to walk back, still wet and getting wetter, in the non-stop rain. A bright spot: the health committee president from the center of town has a son who drives one of the pick-up transports. He knew we had this charla and would probably be walking back, and they met us about 5 minutes into our 30 minute walk to drive us back to the health center. That was super nice, but I couldn’t have felt less accomplished than I did at that moment.

We visited a mid-wife that lived right next door to the health center so Elke could see a home there (and it was one of the nicer ones). Then we walked back to the health center and all put on dry clothes, drank tea, and went to bed. Lucky for Elke and I, we were given the truck cabin as our seats on the way back to town, and were able to sleep. Poor Fletch got stuck crowded in the back under a taurpalin, leaking water here and there, everyone squished tight for 4 hours of bumpy, slow going road.

Arriving in Santa we’d planned to go to our friend Pedro’s house for breakfast then back to the health center for the midwife meeting that had cut our Quixabaj trip short. Then Aurelio told us, really we didn’t need to go to this meeting, there would be another bigger meeting in two weeks where we could give a talk….grrr, ok. So we ate breakfast with Pedro, bought some produce when as the market opened up, and waited for 40 minutes, all of us falling asleep, for the micro to fill up with passengers and take us home. Elke, everyone, this is Peace Corps. Really, there is no better example of the real deal than this. I have yet to understand the oblique communication going on here. I think it’d really help if I could figure it out.

Elke was a total trooper. Our family had a great time talking to her. She had her picture taken with Reina’s baby, as per Reina’s request. Elke wanted to see how people in Guatemala really live. I think she has a good idea now. After a week here, she left to continue south to El Salvador to meet up with more PCV’s working on stove projects there. It was great having you, Elke! Elke was a total trooper. Our family had a great time talking to her. She had her picture taken with Reina’s baby, as per Reina’s request. Elke wanted to see how people in Guatemala really live. I think she has a good idea now. After a week here, she left to continue south to El Salvador to meet up with more PCV’s working on stove projects there. It was great having you, Elke!

Now, see how much fun that was, everyone? Come visit! More stories are one the way. We miss you guys.

Posted by: emily

Saturday, March 7th, 2009 at 9:19 pm

There is more news coming, guys. We haven’t been home much. I feel really lame for not getting anything out. Just give a few more days…

Posted by: emily

Monday, March 2nd, 2009 at 10:57 pm

Yesterday and today we did something entirely new: we traveled about 10 hours to the south to help translate for the Cascade Medical Team. They’re a group of doctors and medical staff from Eugene and Portland Oregon that come one week a year to Guatemala to help the needy poor. A small university just outside of Sololá allows them to take over the campus and set up a field hospital, from which they provide a pretty fantastic array of services, totally for free: general medical consultations, plastic surgery (cleft palate, burns, skin grafts), dentistry, ob/gyn (including surgeries), general surgery (gall bladder removal, hernias, etc.), optometry, opthamology (especially cataract surgeries), and who knows what else.

The whole thing was fascinating and amazing, from the moment we arrived. When we got off the bus, we were greeted by a throng of about a hundred Guatemalans waiting in front of the gate. The armed guard noticed we were white, opened the side gate, and waved us in. All the patiently waiting Guatemalans smiled as we entered, figuring we were probably there to help too. We later found out some of them started the line at 3:00am, nearly 9 hours earlier. The whole thing was fascinating and amazing, from the moment we arrived. When we got off the bus, we were greeted by a throng of about a hundred Guatemalans waiting in front of the gate. The armed guard noticed we were white, opened the side gate, and waved us in. All the patiently waiting Guatemalans smiled as we entered, figuring we were probably there to help too. We later found out some of them started the line at 3:00am, nearly 9 hours earlier.

Once inside, we went looking for Tamra, our contact. We bumped into some friendly doctors wandering around in scrubs, chatted a bit, then eventually found Tamra. “We’re glad you’re here! We have some extra space for you in the dorms. Oh, hey, have you eaten?” she asked, barely taking time to breathe between sentences. “Ok, go over there, that’s the cafeteria, get something to eat, them meet me back here and we’ll find you something to do.” She was off like the wind.

As you might imagine, logistics for setting up a 100-person hospital for a week are pretty complex. We got our first taste of it in the “cafeteria”, a stand-alone gymnasium the kitchen crew had commandeered. They were unloading crate upon crate of food, staging things on steel shelving they’d set up, and a few techs were plumbing gas for a pair of 6-burner industrial stoves. This is where all the hospital and support staff eat for the week. You just show up and get fed. We loved it: real American-style food, all you can eat. For breakfast this morning, they even had bacon! I am ashamed to admit, I went back for fifths, much to the joy and amusement of the cooks. As you might imagine, logistics for setting up a 100-person hospital for a week are pretty complex. We got our first taste of it in the “cafeteria”, a stand-alone gymnasium the kitchen crew had commandeered. They were unloading crate upon crate of food, staging things on steel shelving they’d set up, and a few techs were plumbing gas for a pair of 6-burner industrial stoves. This is where all the hospital and support staff eat for the week. You just show up and get fed. We loved it: real American-style food, all you can eat. For breakfast this morning, they even had bacon! I am ashamed to admit, I went back for fifths, much to the joy and amusement of the cooks.

Once we ate, we looked for work. The medical techs and surgeons spent much of the first day setting up their operatories, but the translators, general practicioners, and optometrists got right to work. Our task on Day 1 was to triage patients; the translators reviewed referral paperwork and spoke with the patients, getting as much data as possible, and the general doctors then decided where the patients needed to go next: some to pre-surgery screening, some to general consultations, etc. The optometrist’s main job the first day was to find some opthamology patients for the eye surgeons to start with on Monday.

It was cool to be able to use my spanish to help people in a direct, tangible way. “This elderly lady says she has has a big painful lump in her abdomen. Should I send her for a hernia consult?” I would ask the triage doctor, Noreen. “Yep,” she would nod, and I’d send the patient on. Noreen was originally form Oregon, but now works as an ER doctor in Chicago. I think I liked her because she reminded me a lot of Julie, my doctor buddy in Oregon. They’re both about the same age and have simliar personalities. It was cool to be able to use my spanish to help people in a direct, tangible way. “This elderly lady says she has has a big painful lump in her abdomen. Should I send her for a hernia consult?” I would ask the triage doctor, Noreen. “Yep,” she would nod, and I’d send the patient on. Noreen was originally form Oregon, but now works as an ER doctor in Chicago. I think I liked her because she reminded me a lot of Julie, my doctor buddy in Oregon. They’re both about the same age and have simliar personalities.  As I was checking in patients, I noticed that those farther back in line were drinking small vials of liquid being dispensed by one of the nurses. “Deworming,” she said, noting my curious look. “We just do it to everyone that even shows up.” She gestured to a HUGE box of deworming medicine I’d not noticed before. For those of you that don’t know, the World Health Organization estimates that one of every two humans on the planet carries roundworm in their gut. Yuk. As I was checking in patients, I noticed that those farther back in line were drinking small vials of liquid being dispensed by one of the nurses. “Deworming,” she said, noting my curious look. “We just do it to everyone that even shows up.” She gestured to a HUGE box of deworming medicine I’d not noticed before. For those of you that don’t know, the World Health Organization estimates that one of every two humans on the planet carries roundworm in their gut. Yuk.

Later that same day, I was helping one of the GPs in the clinic, and I came across the elderly lady again. “I need her to lie down,” Dr. Paul had me explain. He started examining her, touching her abdomen. “Yep, hernia. She has two. Look, I can push it back in.” He explains to me all about hernias, and that he wants to operate on her, as it is obviously causing a lot of pain and affecting her quality of life. “That, and if it should accidentally get twisted, she will die in a few days,” he added. With medical help unavailable most of the time here, that is how it is. I explained all of it to the 85-year old patient and her daughter. I then found out that she walked 2 hours with her pair of protruding hernias just to get here. The doctor was floored. “You have to understand,” I explained to him. “These older Guatemalans are the toughest people on earth. If you ripped her arm off, she would sit there patiently and not complain a bit, waiting for you to do whatever procedure was next.” This stoicism is admirable, but is sometimes their undoing- we saw a glaucoma patient that “just endured” their blinding eye pain for months before seeking medical attention. But by that time, his optic nerve had been killed by all the pressure, leaving him blind beyond even the reach of modern American medicine.

Speaking of eyes, I spent the second day working with optometrists and opthamologists. One of the optometrists demonstrated that sometimes the people best suited to this work are the older doctors. When the first glaucoma patients showed up, the younger optometrist was concerned because she did not have the electronic gizmo to measure eye pressures. “I saw a (the name escapes me) in the pile of equipment in the back room,” she joked. The older optometrist shrugged. “Get it out, I learned how to use one of those in school.” Everyone stared at him, then someone brought out the tool. It was a stainless steel device with weights and a spring guage pointing to a numeric scale. He cleaned it, went over to the reclining patient, and pressed it against his eye. “This is tricky,” he told me. “I will balance it, you read out the scale reading to me as I move it.” Yep, it was gross- but really cool.

Later, I got to help Mary the eye surgeon with a cataract surgery. Here she is at triage, picking up a bunch of patients. When it came time for the actual surgery, I didn’t really do much; there was a second interpreter, so we traded off some. I DID help Mary by using my leatherman to patch up a piece of malfunctioning surgical equipment (not joking here, folks) in the Guatemalan surgery suite. The eye team had a TON of technical difficluties, as the Guatemalan equipment they were borrowing was old hand-me-down from the US and kept malfunctioning. To make it worse, the probes and syringes etc. that they brought with them from the US were packed by a different opthamologist; Mary and Dee (the RN assistant) had to waste a TON of time sifting through boxes and cartions. I could tell Mary was getting pretty frustrated- a surgery that would have taken her 15 minutes in her own suite in Oregon was still not even started after 4 hours of work. And I Later, I got to help Mary the eye surgeon with a cataract surgery. Here she is at triage, picking up a bunch of patients. When it came time for the actual surgery, I didn’t really do much; there was a second interpreter, so we traded off some. I DID help Mary by using my leatherman to patch up a piece of malfunctioning surgical equipment (not joking here, folks) in the Guatemalan surgery suite. The eye team had a TON of technical difficluties, as the Guatemalan equipment they were borrowing was old hand-me-down from the US and kept malfunctioning. To make it worse, the probes and syringes etc. that they brought with them from the US were packed by a different opthamologist; Mary and Dee (the RN assistant) had to waste a TON of time sifting through boxes and cartions. I could tell Mary was getting pretty frustrated- a surgery that would have taken her 15 minutes in her own suite in Oregon was still not even started after 4 hours of work. And I  could see her anxiety that these conditions might cause her to mess up. I felt really bad for her. As Dee was prepping a sterile irrigation machine, Mary started the “eye block”, where they neutralize the nerve so they can work. She whipped out a BIG needle, maybe 3 inches long, and announced “you folks might want to look away if you’re queasy.” The other translator turned, and I leaned in closer to watch her stick that needle RIGHT INTO THE PATIENT’S EYE, all the way up to the hilt. The tough old Guatemalan lady didn’t even complain, but I could tell she wasn’t liking it any. “Did you just stick that through the sphere of her eye?” I asked incredulously. Mary rolled her eyes and sighed. “It’s not sphere, it’s globe. And no, I stuck it around her eye and into the nerve in the back of the socket. I suppose that’s better. I guess. could see her anxiety that these conditions might cause her to mess up. I felt really bad for her. As Dee was prepping a sterile irrigation machine, Mary started the “eye block”, where they neutralize the nerve so they can work. She whipped out a BIG needle, maybe 3 inches long, and announced “you folks might want to look away if you’re queasy.” The other translator turned, and I leaned in closer to watch her stick that needle RIGHT INTO THE PATIENT’S EYE, all the way up to the hilt. The tough old Guatemalan lady didn’t even complain, but I could tell she wasn’t liking it any. “Did you just stick that through the sphere of her eye?” I asked incredulously. Mary rolled her eyes and sighed. “It’s not sphere, it’s globe. And no, I stuck it around her eye and into the nerve in the back of the socket. I suppose that’s better. I guess.

Did I mention that this patient was the same 85-year-old hernia lady I saw the day before? Wow, is SHE going to have a tough week. Did I mention that this patient was the same 85-year-old hernia lady I saw the day before? Wow, is SHE going to have a tough week.

The Cascade Medical Team’s lab technician was also fun. She is from New Zealand, and VERY enthusiastic about her job at analyzing blood. I spend a while talking to her, and she was pretty excited that my parents both used to do the same job as hers. She explained that back when she learned to be a tech, the program was almost as long as med school, and they had to be able to start up a field lab from almost nothing, including blowing their own glassware. (I vaguely remember my mom telling me a similar story). Nowadays, though, most of the lab tech are just computer operators, and without their gadgets, they’re pretty useless. In the next breath, of course, she showed me a gadget she’d brought with her that looked like an oversized calculator.”This thing costs about $10,000 so I’d better not drop it,” she said. She took a drop of blood from a patient, and put it into a special disposable cassette then into the machine. “For $38 a cassette, I get blood sugar, platelet count, and about a dozen other readings just from one drop.”

She then shifted her attention to some ancient-looking Guatemalan microscopes reminiscent of high school biology class. “You seem resourceful,” she continued. “Can you figure out what’s wrong with these microscope bulbs?” I looked. “Well,the filament looks OK, but sometimes they are broken and you can’t see it,” I explained. She frowned, “I just don’t see how they could BOTH be broken.” She puttered off, to look for a solution. I played with the microscopes for a bit, then discovered a well-concealed rotary switch. Click! they worked. The tech returned a few minutes later. “What did you do?” she asked. “Check it out… a switch!” I said. Everyone laughed. We were back in business, ready to search for parasites and high white blood cell counts. I didn’t mention that my mom used to also get mad at me for tinkering with & breaking things. But it paid off- after a childhood of fixing things I broke, now I can fix most anything.

As I mentioned in a post a while back, part of the reason we were involved with this is because of Francisco Juan Fancisco, a guy from our village with serious eye problems. We met him at the front gate, and jumped him ahead of the line and right into a consult with the optometrist. She worked him over pretty thoroughly, dilated his pupils, the whole nine yards. After about an hour of analysis, the optometrist took me aside and explained the situation. “The good news is, his right eye is fine. He shows no signs of a cataract, and his eye irritation is just from environmental stuff like dust, wind, and bright sunlight,” she explained, handing him some artificial tears and a pair of sunglasses. “The other eye, however, is irreparably blind,” she continued. “It appears he had a powerful glaucoma attack that lasted for several months. The pressure cut off blood supply to the optic nerve, killing it. Sadly, we can’t do anything for him.” This was the eye patient I mentioned earlier in the post: he suffered through months of searing eye pain, figuring it would eventually go away and complaining would serve no purpose. But if he’d sought help early on, he could have been treated (assuming treatment was available somewhere) and his eye saved. As I mentioned in a post a while back, part of the reason we were involved with this is because of Francisco Juan Fancisco, a guy from our village with serious eye problems. We met him at the front gate, and jumped him ahead of the line and right into a consult with the optometrist. She worked him over pretty thoroughly, dilated his pupils, the whole nine yards. After about an hour of analysis, the optometrist took me aside and explained the situation. “The good news is, his right eye is fine. He shows no signs of a cataract, and his eye irritation is just from environmental stuff like dust, wind, and bright sunlight,” she explained, handing him some artificial tears and a pair of sunglasses. “The other eye, however, is irreparably blind,” she continued. “It appears he had a powerful glaucoma attack that lasted for several months. The pressure cut off blood supply to the optic nerve, killing it. Sadly, we can’t do anything for him.” This was the eye patient I mentioned earlier in the post: he suffered through months of searing eye pain, figuring it would eventually go away and complaining would serve no purpose. But if he’d sought help early on, he could have been treated (assuming treatment was available somewhere) and his eye saved.

It was difficult for me to explain the situation to Fancisco Juan and his daughter Maria. How do you tell someone that they made that huge journey for nothing, and that his vision can never be restored? I also warned him, per the doctor’s instructions, that if he experienced a similar pain in his remaining eye, he was to go immediately to an eye doctor to get some eye medicine to prevent this from happening again. Francisco and Maria nodded, and walked back with me to the front gate to start their journey home. They thanked me over and over for helping them, and I tried not to feel silly: I really didn’t do anything. “Can you take us to Emily?” they asked. “We want to thank her too.” We found her in the clinic, and while Francisco thanked Emily, I remembered a last piece of unfinished business. “Here’s the 80 quetzales I owe you for the chickens,” I told Maria. Yep, she’s the Chicken Lady. Our little town is full of strange coincidences.

Posted by: jfanjoy

Friday, February 27th, 2009 at 2:54 pm

Photography is a funny thing in Guatemala. In lots of rural places, taking photos of the locals can be downright dangerous. Some of them think that the photo might steal their soul, but the bigger concern is that they often think that you are taking a picture so you can show it around in the US to decide which children would be the best to steal. This is no laughing matter; a few years ago a tourist got stoned to death for picking up a kid in a rural Guatemalan town, because they misunderstood his motives. As odd as this fear sounds, it’s not without some base in truth: there are hundreds of documented cases of women being forced to give up their kids for adoptions, or Guatemalans robbing other Guatemanlans of their kids to forge their papers and place them in adoption agencies (receiving a finder’s fee, of course). It’s a nasty mess, and something we have to be careful about. Photography is a funny thing in Guatemala. In lots of rural places, taking photos of the locals can be downright dangerous. Some of them think that the photo might steal their soul, but the bigger concern is that they often think that you are taking a picture so you can show it around in the US to decide which children would be the best to steal. This is no laughing matter; a few years ago a tourist got stoned to death for picking up a kid in a rural Guatemalan town, because they misunderstood his motives. As odd as this fear sounds, it’s not without some base in truth: there are hundreds of documented cases of women being forced to give up their kids for adoptions, or Guatemalans robbing other Guatemanlans of their kids to forge their papers and place them in adoption agencies (receiving a finder’s fee, of course). It’s a nasty mess, and something we have to be careful about.

However, in our town, they all know us and have decided we’re mostly harmless. You might have noticed we have a lot of pictures in our blog; if we want to take pictures, we ask first, and nowadays they get downright excited about it. For some, it’s the novelty of being photographed. Others want to get a copy (which we usually provide, as a thank-you for letting us get a great picture). The village elders encourage it because they they feel like if they get more stateside exposeure, it increases their chance of getting some international aid. That’s probably a good bet.

This has all had a peculiar, somewhat undesireable side effect. We are now the de-facto “village photographers.” We have a camera, know how to take good pictures, and pass by the photo lab in Huehuetenango every month or so during our travels. In order to keep it under control, we had to set ground rules early on:

1) We need to be paid up front. We just pass our cost on, we don’t mark up. Peace Corps doesn’t allow side businesses. I occasionally think we should charge extra, then use the profits to do a community project. The jury is still out on this one.

2) It needs to be kept on the down-low, so we don’t get swamped with requests.

3) We won’t do it if we have “real” work we’re supposed to be doing at the time.

So what do Guatemalans want with all these pictures? Well, some of it is the normal stuff: our neighbors wanted pictures of their grandkids in the county parade, things like that. But most of it is women and their tiny children, dressed up in their finest traditional garb, taking pictures to send back to their husbands who have been working illegally in the US for the last few years. I guess they don’t want their husbands to be lonely. Maybe they hope the pictures will make them come back? The whole thing is a bit creepy.

And funny. Funny, because Guatemalans have some strange cultural hangups about photos that I’ve never heard of before. The firt one that got us is that they DEMAND that the entire body be visible. Waist-up glamshots are a nonstarter. I took a few like that early on, and the family was baffled as to why I didn’t know how to work the camera correctly, to get their entire body. I was even shown how to use the viewfinder. Hah! The second oddity is that Guatemalans don’t like to smile in photos. And, no, it’s not like American middleschool girls who are shy in front of the camera. Guatemalans are all business during a shoot, so I joke with them, make stupid faces, etc. until they smile, and take a few that way too when they are off-guard. But then when we review them, they tell me to erase any that have smiles. If other family members are around, everyone makes fun of the ones with smiles, as though the person were naked or something. Bizarre.

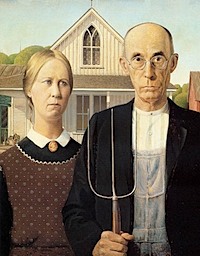

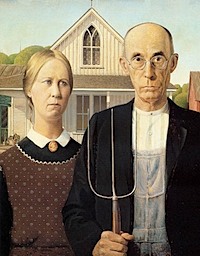

I think of the resulting pictures as “American Gothic“. Here we have have two pictures of Lena, a neighbor. They’re for her husband in the US. The one on the left is quite nice, I think. She hated it. The one in the right is, well, creepy. That is the one she’s sending.

Now you know a little bit about photography in Guatemala. Jim T., Mike G. and Tom F. I think of you guys all the time here.

Posted by: jfanjoy

Wednesday, February 25th, 2009 at 1:39 pm

Now that we’ve returned to the village, life is back to “normal”, whatever that is. Right now, I hear sheep baaaing outside my window. That is normal.

When we go away, it’s easy to forget how pretty it is here. There is a wheat field just above our house. Alberto and Chalio took us there because they said it was neat; they were right. Yesterday, Manuel took us to see the village bread oven we keep hearing about. They use it to make sheka, a traditional semi-sweet bread made with lard. The oven is constructed of clay and mud, and to use it you simply fill it with wood and light it on fire. When the fire is done, you sweep out the coals and start baking. The oven was still warm to the touch from when they fired it yesterday. When we go away, it’s easy to forget how pretty it is here. There is a wheat field just above our house. Alberto and Chalio took us there because they said it was neat; they were right. Yesterday, Manuel took us to see the village bread oven we keep hearing about. They use it to make sheka, a traditional semi-sweet bread made with lard. The oven is constructed of clay and mud, and to use it you simply fill it with wood and light it on fire. When the fire is done, you sweep out the coals and start baking. The oven was still warm to the touch from when they fired it yesterday.

I am back to gardening. The neighborhood kids ran a hose from a nearby river over to my garden so they could water it, completely without any prompting from me. I was very proud of them. In the short time since I took this photo, this batch of broccoli has grown to nearly knee-high. My first batch is starting to go to seed, so I need to harvest the few that haven’t yet, and eat them. I am back to gardening. The neighborhood kids ran a hose from a nearby river over to my garden so they could water it, completely without any prompting from me. I was very proud of them. In the short time since I took this photo, this batch of broccoli has grown to nearly knee-high. My first batch is starting to go to seed, so I need to harvest the few that haven’t yet, and eat them.

Speaking of agriculture, I took a picture of Nas Palas hoeing his field, with the help of Galindo (who is now doing much better). Check out tiny Alberto, age 5, getting in there with his crazy kid hoe. Whenever someone turns over a field, the chickens all converge from wherever they’re wandering in the valley. They know that there are tasty worms and bugs to be found when the dirt is flying. Speaking of agriculture, I took a picture of Nas Palas hoeing his field, with the help of Galindo (who is now doing much better). Check out tiny Alberto, age 5, getting in there with his crazy kid hoe. Whenever someone turns over a field, the chickens all converge from wherever they’re wandering in the valley. They know that there are tasty worms and bugs to be found when the dirt is flying.

Emily is still teaching Lina, Galindo’s sister, how to bake. They usually do biscuits, but sometime they mix it up. Here we see them making gingersnaps. They locals love ’em, even though they’ve never had anything like them before. But they’re not a picky folk. If it has any nutritive value whatsoever, they will probably like it. If it has sugar, they are guaranteed to like it.

This is life in rural Guatemala.

Posted by: jfanjoy

Saturday, February 21st, 2009 at 2:50 pm

…a staphylococcus infection in my throat! We went to see the doctor this morning, and she met with us promptly. “All tests are still negative, except for the throat culture,” she explained, and showed me the lab reports. Now I have been directed to take ten days of Ciprofloxin, a powerful antibiotic that the FDA has only approved for “severe and life-threatening bacterial infections.” Yep, that’s Guatemala for you- they think that something it the right tool just because it is the fanciest and/or most expensive. I see so much antibiotic misuse here; since all medicines are over-the-counter, people even use antibiotics to treat viral infections (which is pointless). I’m sure that the third world is singlehandedly advancing the world crisis in antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains. But I digress. …a staphylococcus infection in my throat! We went to see the doctor this morning, and she met with us promptly. “All tests are still negative, except for the throat culture,” she explained, and showed me the lab reports. Now I have been directed to take ten days of Ciprofloxin, a powerful antibiotic that the FDA has only approved for “severe and life-threatening bacterial infections.” Yep, that’s Guatemala for you- they think that something it the right tool just because it is the fanciest and/or most expensive. I see so much antibiotic misuse here; since all medicines are over-the-counter, people even use antibiotics to treat viral infections (which is pointless). I’m sure that the third world is singlehandedly advancing the world crisis in antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains. But I digress.

Yesterday we went to visit our friend Anne’s site, as it is very close to Xela. She has a nice little apartment in a tiny but friendly village. It was refreshing to spend a few hours with her as she walked us around town, showing off her home. Though she’s had some trouble just like everyone else, she spoke positively and enthusiastically about her town, her coworkers, and the projects she’s working on. It seems like many of our friends are at an emotional low point in there service, so it was a great relief to spend time with someone who isn’t. It makes us feel less guilty that we’re having such a good time too. Yesterday we went to visit our friend Anne’s site, as it is very close to Xela. She has a nice little apartment in a tiny but friendly village. It was refreshing to spend a few hours with her as she walked us around town, showing off her home. Though she’s had some trouble just like everyone else, she spoke positively and enthusiastically about her town, her coworkers, and the projects she’s working on. It seems like many of our friends are at an emotional low point in there service, so it was a great relief to spend time with someone who isn’t. It makes us feel less guilty that we’re having such a good time too.

The only other thing of interest is that we went to a strange bakery yesterday, “Bake Shop.” The locals pronounce it “BAH-kay SHOWP,” as they don’t really understand what it is: a real-life Mennonite bake shop right here in Guatemala. It was delicious, and carried such midwest American favorites as vanilla pudding filled donuts, banana bread, and “whoopie pies”. All were delicious. Here is a picture of Emily telling the workers about how her Menonite nanny used to make them whoopie pies when she was a kid. The only other thing of interest is that we went to a strange bakery yesterday, “Bake Shop.” The locals pronounce it “BAH-kay SHOWP,” as they don’t really understand what it is: a real-life Mennonite bake shop right here in Guatemala. It was delicious, and carried such midwest American favorites as vanilla pudding filled donuts, banana bread, and “whoopie pies”. All were delicious. Here is a picture of Emily telling the workers about how her Menonite nanny used to make them whoopie pies when she was a kid.

OK, tomorrow night we should be back in our village. Thanks everyone for all your emotional support and well-wishing.

Posted by: jfanjoy

Thursday, February 19th, 2009 at 10:21 pm

There is good news, and there is bad news. I was released from the hospital today, ending my three-night imprisonment. The bad news? The doctors are still awaiting lab results, and those reuslts won’t be available until Saturnday morning, so I have to spend three MORE nights in Xela before I can go home. I should try to think of it as a “forced vacation,” I guess.

As for what’s wrong with me, the jury is still out. The doctor came in this morning to examine me again, and the conversation went something like this (translated into English, for your convenience):

Doctor’s Exam, Morning #4:

“Hmm, I see you still have a little fever. Anything else?” the doctor asks, as she starts checking my blood pressure.

“Well, I still have headaches and my throat is a little sore. My biggest problem is boredom; I’m going nuts in here,” I reply.

She nods, ignoring my last complaint. “Well, all of your tests are still negative. We really don’t know what’s wrong with you, so we’re running a throat culture and additional blood tests to be sure. Those results won’t be available until Saturday.” No no no no no no no

“But I think we can let you go today, if you stay in town a few days and come back here Saturday morning for a consultation,” she finished.

YES! wait…. I can’t go home until Sunday? Argh. Then she let the air out of the sphygmomanometer. “It seems your blood pressure is high.” No shit, Sherlock, I’m SICK! I think to myself. “Do you eat a lot of salt? You need to cut salt out of your diet.”

I took a deep breath to control my annoyance. I KNOW my normal blood pressure is within healthy limits, as I’ve been passing FAA flight physicals for my pilot’s license since 1998. “Well, we don’t use salt when we cook. At all. When we take food to the neighbors, they complain and add it,” I responded with a fake smile. Apparently this annoyed Emily too, as she takes pride in making quality, healthy food. She was thinking something far ruder: “If you want to cut salt out of his diet, you can stop feeding him the crappy hospital food here!” Yeah, everything except the orange juice was salty like bar peanuts.

The doctor placed her exam articles in her lab coat and shook my hand, congratulating me on my partial recovery and subsequent escape from the hospital. “And when we meet on Saturday, we can talk about which blood pressure medication to start you on.”

Whatever. Whatever.

The nurses gave me some painkillers (Naproxen this time) then we made our escape. We dropped our backpacks at our favorite hostel, then headed straight for Casa Babylon, a restaurant that serves the only GOOD burgers in Xela. I had a cheeseburger, chips, and a brownie with ice cream. Emily had a giant spinache salad and a big plate of California rolls. Basically, we pigged out. It felt good to finally eat something substantial after being sick for a week.

Hopefully, this stupid drama is now all but over. I will send out a note on Saturday to let everyone know how the tests came out. Besides that, I will get back to normal posts (if there is such a thing).

Posted by: jfanjoy

Wednesday, February 18th, 2009 at 12:24 pm

The specialist appeared last night and poked and prodded. He seemed competent and thorough, like my primary doctor. We chatted for several minutes, as he explained all the diseases they’d already ruled out; things like malaria, dengue, cystoplasmosis, measles. I was only mildly releived; I was already pretty sure I didn’t have any of these. “We are still waiting on the results of the bile test,” he continued, “But if that comes back negative as I suspect it will, then what you probably have is a self-terminating virus of some sort that is runnung its course.” And there really isn’t a way to treat that, you just have to be patient. The specialist appeared last night and poked and prodded. He seemed competent and thorough, like my primary doctor. We chatted for several minutes, as he explained all the diseases they’d already ruled out; things like malaria, dengue, cystoplasmosis, measles. I was only mildly releived; I was already pretty sure I didn’t have any of these. “We are still waiting on the results of the bile test,” he continued, “But if that comes back negative as I suspect it will, then what you probably have is a self-terminating virus of some sort that is runnung its course.” And there really isn’t a way to treat that, you just have to be patient.

This morning my regular doctor returned, and said basically the same thing. Another option they are now looking at it mononucleosis. “We are still waiting for lab results,” she said, repeating the never-ending mantra, “so we need to keep you for observation until we get those.” Oh no.

“How long will that take?” I asked, dreading the answer.

“Some will come in Friday, others tomorrow,” she said. [ death wail inside my soul ] “But we might be able to discharge you tomorrow. We’ll see.” So, yeah, my sentence is now extended. The good news is that I feel a lot better; my fever is low, I am active today, and am eating better. That’s largely Emily’s credit, as she skips out occasionally to bring me back healing foods: yogurt, cream-filled donuts, chocolate milk, Subway sammiches, and (rumor has it, dare I hope?) a personal pan pizza from Pizza Hut. Honestly, when the refried beans and scrambled eggs with a slice of white bread toast hits the table, all I can do is push it around with a fork. You’ve heard of bad hospital food? Now imagine it’s prepared in a 3rd-world country.

We’ve been away from our village for so long that I have this concern our natives will start to forget who we are, or think that we don’t like them anymore. It’s worse because we are going to be on the road a LOT in March, with two projects, two conferences, the eye guy, and a friend coming from the US for a little traveling. I’d really like to get back home as soon as possible.

The one positive thing about this is that they said I can keep my radiographs. I want to show the lung x-rays to the villagers, to explain what lungs look like and what they do. When we did a charla on the effects of smoking, we discovered that they really don’t have a firm grasp of what a “lung” is. In fact, in Q’anjob’al there isn’t even a word for this body part.

Posted by: jfanjoy

Tuesday, February 17th, 2009 at 4:49 pm

So, yeah, I am still in the hospital. I have a low fever, high white blood cell count, and nobody knows anything more. The PCMO tells me they are basically keeping an eye on me to rule out some of the more exotic central american diseases. I am getting pretty tired of being here. I hear rumors that a communicable diseases spcialists is going to see me this afternoon. I’ll let you know how that goes.

I am pretty tired of my cell, so I went into the hospital courtyard today. It’s warm and sunny, cloudless, perfect. The topiary in the middle is shaped like a Quetzal, the national bird of Guatemala. Very clever! The grass is golfing-green height and comfy, so I took a little nap. Later, I came back and did Tai Chi in the courtyard when no one was looking. That made me feel a little less cooped up, I suppose. I am pretty tired of my cell, so I went into the hospital courtyard today. It’s warm and sunny, cloudless, perfect. The topiary in the middle is shaped like a Quetzal, the national bird of Guatemala. Very clever! The grass is golfing-green height and comfy, so I took a little nap. Later, I came back and did Tai Chi in the courtyard when no one was looking. That made me feel a little less cooped up, I suppose.

I have a competent-seeming doctor, but still have little faith in the friendly but inept nursing staff. I REPEATEDLY told them they can’t get an accurate temperature reading if they take it right after I had a glass of water. Eventually, on the PCMO’s recommendations, I waited 15 minutes and walked up to the nurses’ station.

“Hi. I’d like you to take my temperature, please,” I said.

Baffled look. Flips through chart. “We just took it 15 minutes ago, at noon. You’ve been at 36.5 all morning.” (for those not Celsius-oriented, that’s BELOW normal)

“Humor me. I will go back to my room if you do.”

So an intern shrugged, whipped out a thermometer (they still use glass ones here) and took my temperature. “38.2!” he exclaimed. “You’re fever is back!” the nurse added.

No duh, retard. So I spent a few minutes telling them AGAIN that they can’t get accurate readings unless they warn me 15 minutes before, and I stop drinking the water. I drink a lot of water, you see, a holdover from when I almost died of heat stroke at summer camp. (that is another story entirely)

I hope I get to leave tomorrow. Apparently they are waiting until at least then, to see the result of some blood/ hemoglobin/ bile test they took yesterday. My Spanish failed me at one point, so I can’t be more elaborate.

Posted by: jfanjoy

Monday, February 16th, 2009 at 5:01 pm

It’s been over 20 years since I spent any quality time in a hospital, so I don’t have a good basis of comparison. I think I am a grumpy patient, I get that from my Dad. They just came in to take three MORE vials of blood and 4 more slides. Either way, I am cool as long as they only take stuff OUT, and don’t put anything IN. I have no trust of hospitals. They can have all the blood and poop they want, and X-rays are pretty noninvasive. But when they first mentioned a body-cavity exam, I jumped out of bed and was going for my backpack. Luckily, I asked for clarification, and found out that “body cavity search” in Spanish means you get an ultrasound… a little different than in the USA.

Then the wheelchair showed up to take me to the ultrasound. “Um, I’m not getting in that thing,” I told the baffled looking nurses. “Come back when I’m 80 and we can talk about it.” The second bit at least made them chuckle, and they let me walk myself.

The ultrasound tech was friendly, and basically checked out all the organs I know the words for in Spanish… and a few I don’t. He said that they all looked fine, and that he hadn’t seen anything in the X-rays either. (I checked his lab coat, and he’s also the radiologist, apparently.) He DID find and photograph an anomaly on my vesícula biliar, though, but he said it probably isn’t anything I should worry about.

But guess what, I did worry! That was the one organ he mentioned that I didn’t know the English for. I returned to my laptop, and confirmed my guess: gall bladder. Ironically, my dad just had his removed less than 2 months ago. Nothing will probably come of it, but I can’t help wonder if they would do surgery for that here, in Guatemala City, or if they would medevac me to the military base in Panama? Blech.

But, in general, I can’t complain too much about the care I am getting…yet. Sure, the instrument tray is rusty, the rooms are without heat and straight from the 60s, and they use mercury thermometers right after I’ve had some water… but I can let that slip. The nurses are friendly, the doctors are willing to talk, and they use disposable syringes and lancets. Lets hope it stays this friendly.

Posted by: jfanjoy

|

|

|

here. The Stove Team’s most prominent stove model is quite different from the one the Peace Corp usually uses, so we thought we’d go learn about options. Turns out we met a really fun, energetic group of people, and then we kidnapped their intern, Elke…Here she is in a happy picture with us, on the hotel roof deck looking out over the city, shortly before the incident.

here. The Stove Team’s most prominent stove model is quite different from the one the Peace Corp usually uses, so we thought we’d go learn about options. Turns out we met a really fun, energetic group of people, and then we kidnapped their intern, Elke…Here she is in a happy picture with us, on the hotel roof deck looking out over the city, shortly before the incident. The stove team had lots of things to do that didn’t involve us, so we had some time to do something we rarely do in Antigua–sight see–as we waited for the right moment to steal away with the intern. People should come visit us because this country is really amazingly beautiful, with some cool stuff to do. So here is a picture to entice you. This mostly goes to my sister who wants to go to Mexico for her birthday, and my brother who wants to go to Belize for his honeymoon. Really guys? Really? You won’t get personal tour guides there (and I’ll probably be annoyed with you forever)…Volcanos, Mayan ruins, rainforests, ocean fronts to the Atlantic and the Pacific, mountains, scuba diving, hiking, canoing through the mangroves, kayaking, zip lining…

The stove team had lots of things to do that didn’t involve us, so we had some time to do something we rarely do in Antigua–sight see–as we waited for the right moment to steal away with the intern. People should come visit us because this country is really amazingly beautiful, with some cool stuff to do. So here is a picture to entice you. This mostly goes to my sister who wants to go to Mexico for her birthday, and my brother who wants to go to Belize for his honeymoon. Really guys? Really? You won’t get personal tour guides there (and I’ll probably be annoyed with you forever)…Volcanos, Mayan ruins, rainforests, ocean fronts to the Atlantic and the Pacific, mountains, scuba diving, hiking, canoing through the mangroves, kayaking, zip lining… Elke was a total trooper. Our family had a great time talking to her. She had her picture taken with Reina’s baby, as per Reina’s request. Elke wanted to see how people in Guatemala really live. I think she has a good idea now. After a week here, she left to continue south to El Salvador to meet up with more PCV’s working on stove projects there. It was great having you, Elke!

Elke was a total trooper. Our family had a great time talking to her. She had her picture taken with Reina’s baby, as per Reina’s request. Elke wanted to see how people in Guatemala really live. I think she has a good idea now. After a week here, she left to continue south to El Salvador to meet up with more PCV’s working on stove projects there. It was great having you, Elke!